Flamer

Summary

Flamer by Mike Curato follows Aiden Navarro, a Filipino American middle schooler spending the summer at Boy Scout camp in the 1990s. During those weeks, he struggles with bullying, body image, and the growing realization that he is gay, all while trying to make sense of his feelings within his Catholic upbringing. As the days pass, Aiden’s loneliness and self-doubt deepen until he begins to question whether life is worth living. Through moments of connection and quiet strength, he starts to accept himself and to understand that his story is still unfolding.

Cultural Analysis

I did not like this book. I read gay fiction almost exclusively now because I am tired of heteronormativity, but I also only read happy gay stories. I grew up much like Aiden, in a conservative Christian community, not Catholic, and I was overweight, which I still am today. My friends, when I had them, were girls. We moved a lot when I was a kid, and I never felt like I fit anywhere. That is where the similarities between Aiden and me end. I didn’t have guy friends and never got along with boys my age. They called me girly, though thankfully never a faggot, at least not to my face. There was no hope in those years, and I remember wanting to die quite a bit, but not the way Aiden does. I never wanted to take my own life. I just wanted God (I was a believer then, though I am an atheist now) to end it for me and I remember asking for that one particularly fraught time in my life and believing that if I had given the word I would have died that night. That kind of quiet despair sits deep inside you when the world keeps telling you that who you are is wrong.

This book feels true to life, and maybe that is why it hurt to read. It captures the suffocating loneliness of growing up queer in an environment that refuses to see you. But it is not a book that would have helped me as a young, closeted kid. I think it would have made me more distressed, because while Aiden’s story ends on a hopeful note, I would not have believed that hope applied to me. He finds some level of acceptance in the end, but I know I would have seen what I saw in my own life: no one accepting me, no one really liking me, and no one wanting me around. It would have felt like one more story where someone else got to survive, but I didn’t see a way that I could. I couldn’t imagine the life and happiness I have now with my husband.

For me, the thing that saved me wasn’t people at all. It was music. I started playing piano when I was about nine, and it became the one place where I could pour everything I felt but couldn’t say. Later, I joined a youth orchestra and learned to play violin. The notes, the rhythm, the structure—they gave me something to hold onto when everything else felt uncertain. Music didn’t judge or demand that I change. It was the first space that let me exist exactly as I was, without apology or shame. I don’t play anymore. I was a piano performance major in college until I failed my first practicum. After that, I switched to piano pedagogy and paired it with English Literature, but eventually I dropped music altogether. Now playing is too painful. It brings back memories of how much of myself I had to hide during those years, how hard I fought to belong, and how deeply I tied my worth to being perfect at something. What once saved me now reminds me of everything I endured to survive.

Still, I can understand why Flamer matters. It is honest about what it means to be young, scared, and queer in a world that keeps trying to silence you. It is not a story I needed then, and it is not one I want now, but it may reach someone who is ready to see their pain named out loud. For readers who still need to know they are not alone, Flamer might be that lifeline. For those of us who already lived it, the book is a reminder of just how far we have come, and how deeply those early wounds still shape who we are.

At the same time, it makes me think about how necessary it is to have many kinds of queer stories available. Some need to show survival and pain because that is where some readers still are. But others, like the stories I choose to read now, need to show joy, love, and not just the possibility of happiness, but actual happiness. Representation is not just about seeing ourselves in our suffering, which is what gay fiction has been for so long. It is about seeing who we can become once we make it through and about showing the world as we would like it to be.

Literary Quality

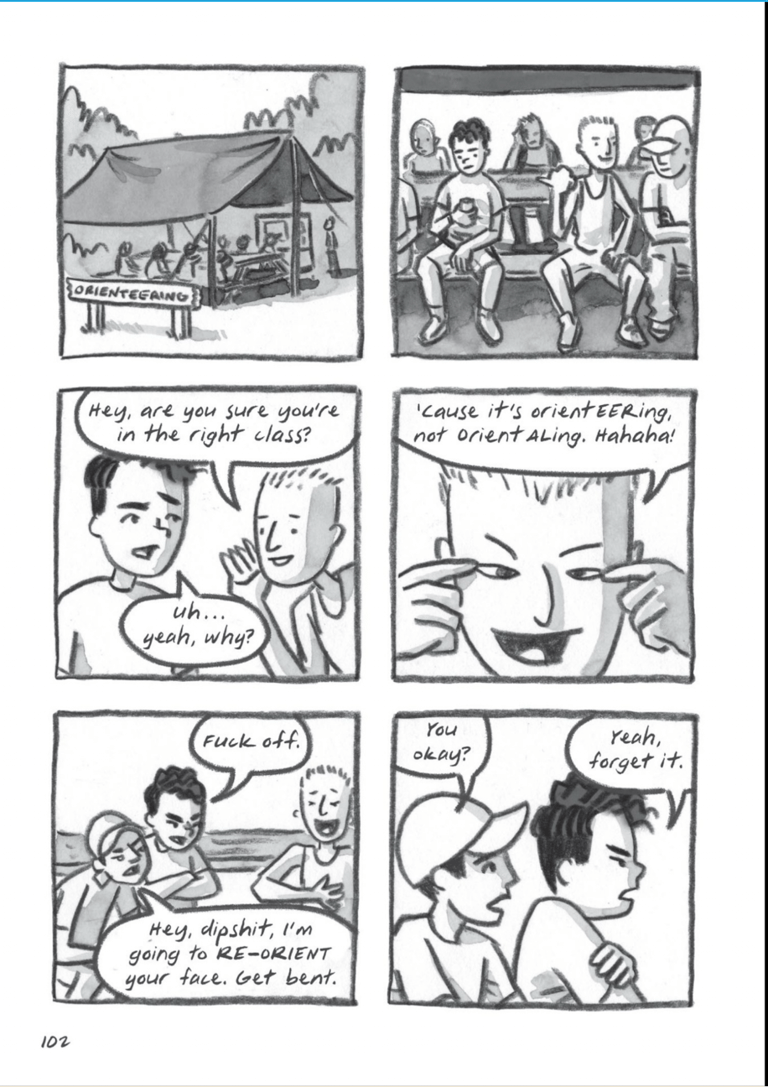

The language in Flamer isn’t literary in any traditional sense. It’s written in the raw, everyday speech of middle school boys, full of slurs, insults, and uncomfortable honesty. The dialogue on these pages captures that perfectly. There’s no polish or poetic phrasing; the power comes from how ordinary and cruel the language feels. Aiden’s world is full of casual racism, sexism, and homophobia, and Curato doesn’t soften that for the reader. It reads like real life, not literature. That choice makes it effective for what it is—a realistic portrayal of how kids talk and how that language shapes someone’s sense of self—but it also limits the book’s literary depth. The writing serves the emotion and truth of the story rather than artistry.

The scene below is a good example of how Flamer uses simple dialogue to capture the cruelty and casual racism that Aiden experiences. The boy’s mockery of Aiden’s Asian heritage is presented without commentary or stylization, which makes it feel disturbingly real. The humor is crude and immature, and the language reflects how prejudice often hides behind “jokes.” Aiden’s quick anger and then his retreat into silence show the isolation that follows this kind of everyday discrimination. The plainness of the language and art together make the moment hit harder. It really feels like something that could happen anywhere, to any kid who stands out.

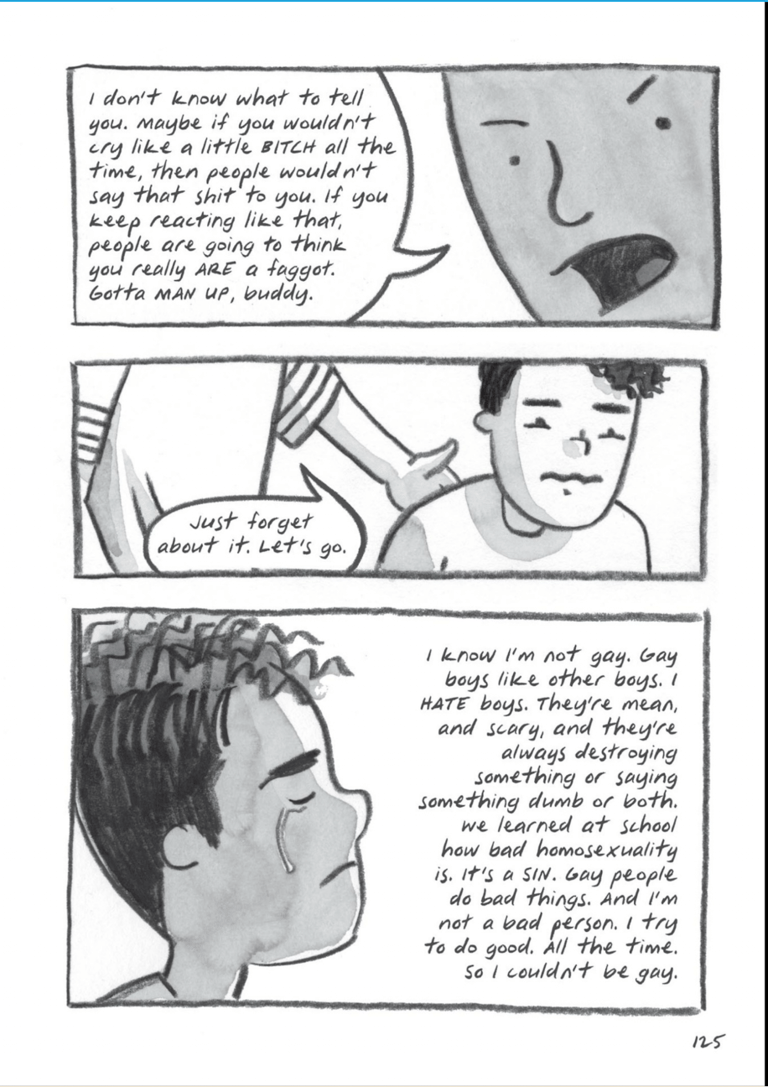

This scene below captures one of the most painful parts of Flamer: the internalized homophobia Aiden has absorbed from his environment. The language is blunt and harsh, mirroring the verbal abuse he hears from others and the voice of shame that begins echoing inside his own head. The dialogue reflects the toxic masculinity that surrounds him as he is told to “man up” and stop crying, as if emotion itself is weakness. Curato’s choice to let Aiden’s thoughts unfold in plain, almost childlike handwriting makes the moment even more devastating. It shows how early and deeply this kind of thinking takes root. There is no lyrical writing here, only the unfiltered confusion of a boy trying to convince himself he isn’t something he has been taught to hate.

Language/Speech

The language in Flamer is intentionally harsh, but one of the hardest words to read is “faggot.” It is used casually and cruelly by Aiden’s peers, echoing the way homophobic language circulates among boys to police masculinity and identity. As someone who has been called that word repeatedly, even as an adult teacher to the point that I had to transfer schools after failed Title IX investigations, it is not just uncomfortable to see. It is triggering. The word carries the weight of real harm, not only because of what it means but because of how it is used to dehumanize.

In the book, the slur exposes how Aiden internalizes shame and self-hatred, but for readers like me who have lived through that language, it is almost unbearable. I understand why Curato included it, because sanitizing it would have softened the reality of Aiden’s world, but that choice does not make it easier to face. I have tried to reclaim the word in my own life. My husband and I sometimes use it with each other to take its power back, but seeing it on the page in the mouths of bullies strips away that reclamation. It brings me right back to the hallways where I could not even walk to my classroom without being harassed.

The use of “faggot” here is realistic, but realism comes at a cost. It is a word that exposes how language can wound and linger long after the moment passes. For some readers, it may illuminate the cruelty queer youth face. For others, it may simply remind us how much pain we have had to survive.

Characters

Aiden is a deeply conflicted and painfully realistic character. He wants to be good, to be accepted, and to live up to the expectations placed on him by his peers, family, and faith, but he constantly feels like he is failing. He carries the weight of shame, loneliness, and confusion, all while trying to understand who he is in a world that keeps telling him who he should be. This panel shows how that pressure has built up inside him until it erupts. His anger is not directed at others so much as at himself for never being “normal” enough to belong. Throughout the book, Aiden’s struggle is not just about sexuality but about identity, self-worth, and survival. He is not an idealized protagonist but a painfully human one, who is flawed, frightened, and desperate to find peace within himself.

Cultural Background

Aiden’s cultural background plays a major role in how he understands himself and the world around him. He is a Filipino American boy growing up in the 1990s, caught between two cultures that both emphasize obedience, family honor, and faith. His Catholic upbringing teaches him that being gay is a sin, while American masculinity tells him that showing emotion makes him weak. These overlapping pressures create a kind of cultural and emotional suffocation. The expectations of being a “good son,” a “good Christian,” and a “real man” all clash with who he actually is. His identity as a person of color in a mostly white environment adds another layer of isolation, as he faces casual racism along with homophobia. Aiden’s story reflects how cultural identity and sexuality can become intertwined sources of conflict, especially for young people who grow up in communities where conformity is prized and difference is punished.

Author photo of Mike Curato from his official website. Used under fair use for educational purposes.

Lifestyle

Aiden’s lifestyle reflects the structure and expectations of a boy growing up in a conservative, middle-class environment in the 1990s. He spends his summer at Boy Scout camp, a setting meant to teach discipline, teamwork, and traditional masculinity, qualities he struggles to embody. Outside of camp, his life revolves around school, family, and church, where obedience and respect for authority are emphasized above self-expression. He has few close friends and often feels more comfortable around girls than boys, which only deepens his sense of being different. His routines are shaped by other people’s rules rather than his own choices, leaving little space for exploration of who he actually is. Everything about his life is designed to mold him into what others think a “normal” boy should be, which makes his quiet acts of resistance, his thoughts, his emotions, his refusal to fully conform, feel both small and revolutionary.

Artistic Quality

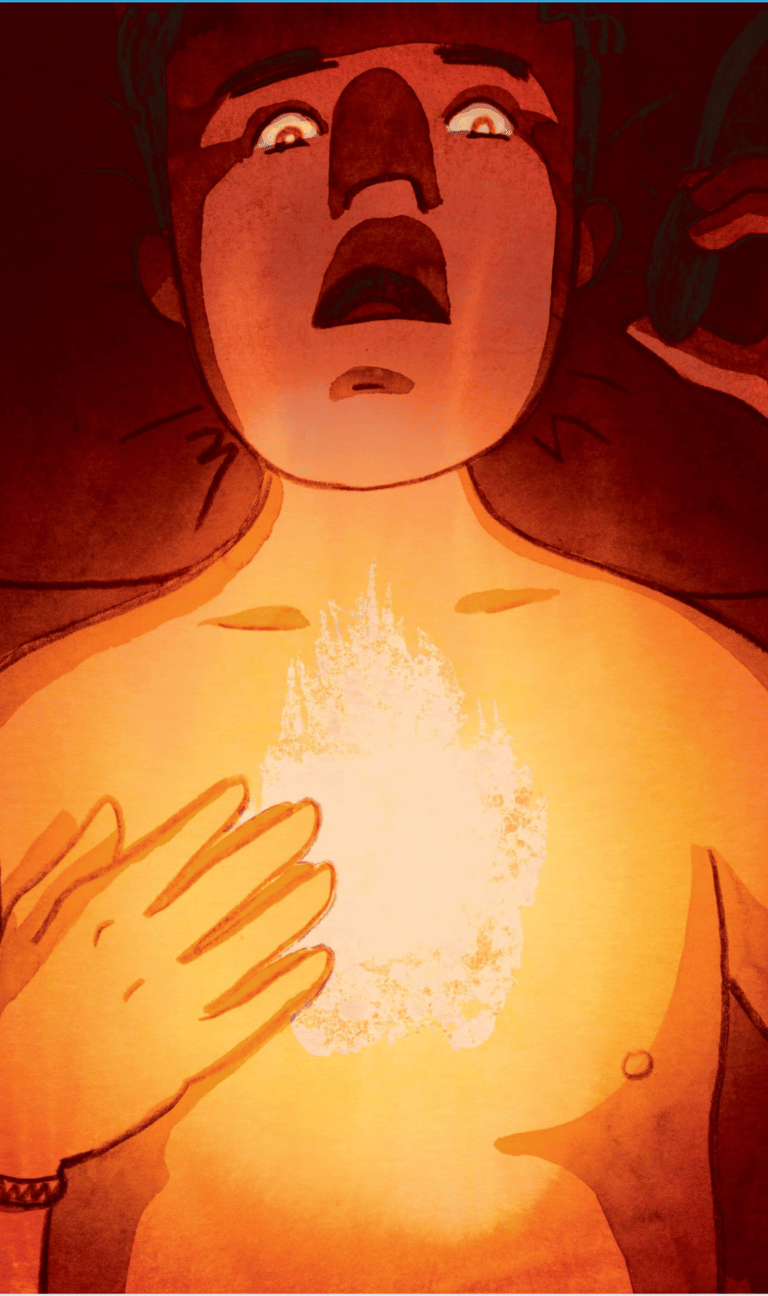

The artistic quality of Flamer is one of its strongest features. Most of the novel is illustrated in shades of black, white, and gray, reflecting Aiden’s emotional numbness and the muted world he lives in. Everything feels subdued, like the color has been drained from his life by shame, fear, and self-denial. However, in moments when his emotions erupt, when his anger, pain, or truth can no longer be contained, the pages burst into reds, yellows, and oranges. These colors feel like fire, representing both destruction and honesty. They are the moments when his true self forces its way to the surface, even if it comes out as rage or despair. The use of warm color against the otherwise monochrome background makes these scenes feel raw and alive. It shows that beneath Aiden’s quiet exterior burns a fierce need to be seen and accepted. The color becomes a visual language for emotion, giving readers a visceral sense of the turmoil inside him.

Illustration Purpose

The illustrations in Flamer are what make the story hit as hard as it does. Since it is a graphic novel, the visuals carry as much meaning as the words, helping readers feel Aiden’s world instead of just reading about it. The art isn’t idealized or polished, and that’s part of what makes it powerful. It shows what life really looks like for a young teen who is scared, confused, and trying to figure out where he belongs. The characters are drawn simply, which makes their emotions stand out even more. There’s nothing pretty about these pages, and that’s the point. The world Aiden lives in isn’t kind or forgiving, and the art reflects that perfectly. In moments like this one, when the page fills with light and color, it feels like we’re seeing something break open inside him. The illustrations make the story feel raw and real, like we’re being invited to see the parts of growing up that most people would rather look away from.

Interior page from Flamer by Mike Curato. © Henry Holt and Company, 2020. Used under fair use for educational analysis and commentary.

Purpose

The purpose of Flamer is to show what life can feel like for young people who are struggling with identity, faith, and self-acceptance, and to remind them that they are not alone. Mike Curato wrote this story to reflect his own experiences growing up, caught between religious guilt and the fear of being different. It is meant to speak to those who see themselves in Aiden, who have been told that who they are is wrong, and who need to see someone survive that kind of pain. While it does not shy away from showing the loneliness and cruelty that come with being queer in an unaccepting world, it ends with a quiet sense of hope. The book’s purpose is not to idealize life but to make readers who are like the author feel seen and to show that even in the darkest moments, it is possible to keep going.

Insider/Outsider Status

Mike Curato writes Flamer as an insider, and that perspective is what makes the story feel so authentic. The book is based heavily on his own experiences growing up as a queer Filipino American boy in the 1990s, trying to reconcile his faith with his identity. Because the author lived through so many of the same struggles that Aiden faces, the emotions in the book ring true from start to finish. The fear, the shame, the isolation, and even the small moments of hope all come from a place of lived experience. This insider status gives the story its honesty and emotional depth. It is not an outsider imagining what this life might feel like; it is someone who has survived it showing what it really was.

Conclusion

This is not a book I would recommend for anyone younger than high school. It might be suitable for mature 8th graders, and I can understand why some educators or librarians might want to include it for younger middle schoolers who are beginning to think about identity and belonging. But it is absolutely not appropriate for elementary students, even at the 5th grade level. The language is too crude, and the subject matter too heavy, even though it does reflect how middle schoolers sometimes talk and act. Flamer is raw, emotional, and painfully honest.

As an adult who has lived through similar experiences, this book hit hard. It brought back memories I thought I had long since processed. I never struggled to accept that I was gay. I knew who I was, even as a kid, and I knew it was not something that could be changed, though I remember praying that it might. My pain came not from being gay, but from being in places where I could not be open about it. I was not afraid of myself; I was afraid of the rejection that always followed when others found out. Reading Flamer forced me to relive that quiet, exhausting act of hiding, and the loneliness that came with it.

I can see why this book might save lives for some readers. For those who still need to see themselves reflected honestly, it might be the first time they feel visible. But for someone like me, who already lived that kind of isolation and survived it, the book felt more like reopening old wounds. It resonated too deeply, and it hurt. I respect what Curato set out to do, but I do not need to walk through that pain again to understand it.Flameris an important book, but not a comforting one. It may help others find hope, yet for me, it was a mirror I did not want to face again.